A while ago I’ve spent significant time researching and implementing a fast Hopscotch hash table for C++. My current source code can be found in my github repository at martinus/robin-hood-hashing. After spending some time optimizing, I am mostly happy with the results. Insertion time is much faster than std::unordered_map and it uses far less memory.

Benchmarks

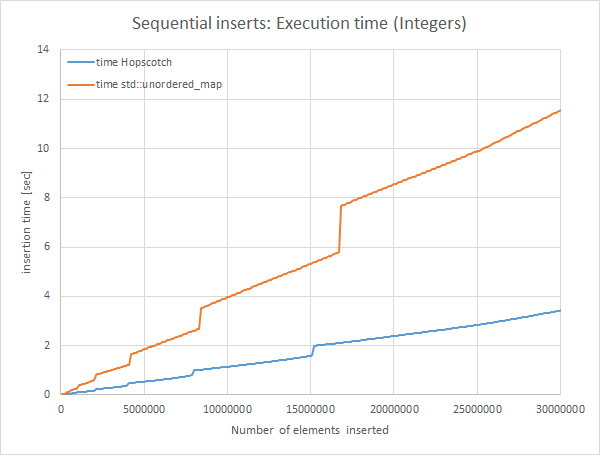

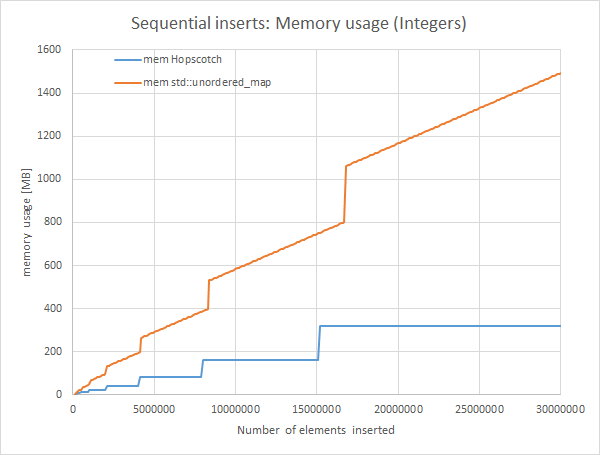

In this simple benchmark I have measured time while sequentially adding an entry (int -> int) to the hashmap, similar to incise.org’s benchmark. As a hash function, I am using std::hash:

Whenever a jump occurs, the hashmap got too full and it is reallocating. Interestingly, std::unordered_map has to allocate memory whenever it inserts an element (since it’s a linked list), while the Hopscotch hash table only allocates once and uses that memory.

I am using Visual Studio 2015 Update 3, 64 bit, Intel i5-4670 @ 3.4GHZ. Here is a comparison table (best values bold)

| Hashtable | Time insert 30M integers | Memory insert 30M integers | Time query 30M existing | Time query 30M nonexisting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| unordered_map | 11.56 sec (100%) | 1493 MB (100%) | 1.84 sec (100%) | 1.92 sec (100%) |

| Hopscotch | 3.44 sec (30%) | 321 MB (22%) | 1.50 sec (81%) | 1.48 sec (77%) |

Insertion is really fast and much more efficient, query time is also a bit faster than std::unordered_map, even though we need to check the hop bitmap of 32 elements.

Robin Hood Hashing vs. Hopscotch

After contemplating a while, I have come to the conclusion that Hopscotch is just a bad version of Robin Hood Hashing. Here is my reasoning:

-

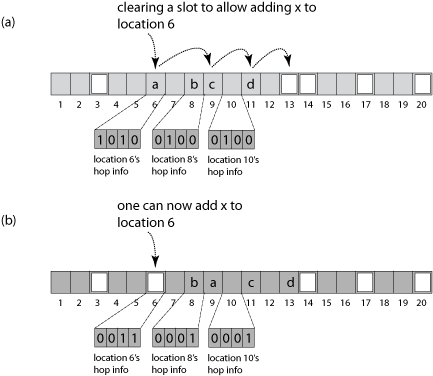

Hopscotch’s bitmap naturally has to be quite sparse. For a perfectly full hashmap, where each bucket contains a corresponding entry, of the 32 hop bits there will be just a single bit that is set to 1. Wikipedia has a nice representation:

-

Is there a better way to represent the hop bitmap? On way would be a linked list of offsets. Unfortunately, linked lists are not very cache friendly.

-

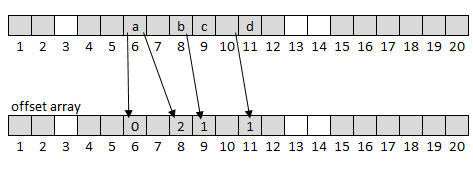

To store the linked list more efficiently, we can put them into an array. How about just storing the offsets next to the buckets? So the above example from a) could be stored like this:

Will this work? Surprisingly, yes! When querying for an element, we just need to sequentially check the offsets. Say we want to check if

bis in the map:- We hash

band get index 6. - The offset at index 6 is 0: That means at index 6 is an element that actually belongs there: It’s not

b, so we have to continue checking. - At index 7 we would expect an offset 1 if it contains an element that was indexed to 6. Since it is taken by something else, it will have a higher value, so we are certain this is not the bucket we are looking for.

- At index 8 we expect an offset 2 if it contains an element that was indexed to 6. It is to, so check the value, and bam! We found the element.

If we query an element that is not in the map, we just need to check hop size offsets.

- We hash

-

All this sounds increasingly similar to Robin Hood Hashing. Once we have the offset, we can use it as clever as robin hood hashing does: It enables us to use the cool “take from the rich” algorithm. So now we can ditch the hop size, and just keep swapping elements exactly like robin hood hashing does.

What now?

With these insights, I believe I have a great idea to implement a highly efficient variant of the robin hood hash table, that takes some ideas from the hopscotch implementation. In my next post, part 2, I will explain these ideas and (hopefully) have a fantastically fast and memory efficient hash table in my repository.